“If you die in-game, then you die for real.”

The proclamation rings through my head as I lay down in a pool of blood. One minute me and my adventuring party were celebrating defeating this area’s boss and getting rare loot, the next we were splayed on the ground. We were helpless as paralysis poison worked its way through our bodies, rendering us helpless to the Player-Killers waiting to ambush us with greed in their eyes and murder in their minds. My mind starts to flash through memories of my life before and after being trapped in this virtual world – of my wife and children who I’ll probably never get to see again, of my co-workers who I have not met in a while and will never get to meet again, and finally of the party members who I have survived with in this harsh landscape so far. My mind races to try and relish these memories one last time as I see the looming shadow of the Player-Killer about to bring his blade down on my neck.

Sword Art Online is one of the more popular anime when it comes to the genre of virtual worlds, spanning three seasons and multiple movies and spin-off series as of the time of writing. The appeal is easy to see as it has elements of action to attract those looking for flashy fight sequences, as well as elements of romance and drama to attract those looking to witness the breadth of human emotion characters go through on-screen.

“If you die in-game, then you die for real.” That is the proclamation that Sword Art Online’s primary antagonist gave during the very beginning of the first season during the Aincrad arc. The ramifications of this statement do not take long for the trapped players to process as waves of dread and panic go through the crowd. If any player’s avatars get killed while the final level of the game is still uncompleted, then those players will have their brains fried by the NerveGear Neuro-VR headset they use to interface with the game.

As early as episode 4 of season 1, we are introduced to the concept of player-killing in SAO. In this particular episode, we are introduced to a guild called Titan’s Hand whose members commit various crimes in order to get ahead of other players, the most notable crime of which is player-killing. Player-killing is when players willfully perform acts of aggression against other players resulting in the latters’ deaths. The killer is implied to be able to loot the victim’s belongings after. In the next episode, another guild composed of player-killers is introduced: Laughing Coffin. In this episode, we learn of a plot involving a married couple and a rare ring loot drop. Without giving away any spoilers, the guild Laughing Coffin was contracted to carry out a murder on a player named Griselda. As you can imagine, the NerveGear headset ended the life of Griselda’s player when their avatar died in-game.

“A member of Laughing Coffin.”

It is well-established that when player avatars die in the game the players themselves die in the real world as well, and the Player-Killers, or PKers for short, know this. There are some, however, that use mental gymnastics to justify their violence against others. The Titan’s Hand guild leader even stated during episode 4 of season 1 that “there’s no proof that killing someone here means they die in real life.” However, when flipped on its head, there is also no proof that Kayaba Akihiko, SAO’s creator, was lying when he made the proclamation in the earliest episode of the show – If you die in-game, then you die for real.

The motivations that a PKer can have for engaging in willful violence against a fellow player can be varied – with some engaging in PK as an act of survival against otherwise insurmountable odds against other players, and others engaging in premeditated murder against targets they have selected. An example of this can be found in episode 10 of season 1 with Kuradeel, a member of the Knights of the Blood Oath guild that has bad blood with Kirito after the latter defeated him in a duel. He is shown using his Laughing Coffin PK guild bag of tricks to isolate Kirito, render him helpless with a paralysis potion, and come within a hair’s breadth of killing Kirito.

Although PK is sometimes justified in a utilitarian respect, some questions one must ask themselves if one were to engage in PK would be:

- What if the player I am about to kill holds some degree of importance to a guild-alliance I belong to? What if their sudden death causes turmoil and potential suffering for others that I care about in the near future? Are my reasons for engaging in PK still justified?

- Is PK my first or last option in this scenario? Why or why not?

- During times when I feel that PK is the only course of action left, is there really no other method I can come up with to tackle the problem I believe I am solving through PK?

- What if I personally know the player whose avatar I am about to kill? Would that make a difference? Why or why not?

- Would thinking about the friends and family of my potential PK victim convince me to try a different method closer to non-lethal neutralization? Why or why not?

Player-killing in virtual worlds has been examined in other media as well, such as in SAO’s spiritual cousin Log Horizon. The premise of Log Horizon is similar, with the individual consciousnesses of a large population of players of a popular Neuro-VR MMO finding themselves trapped within a game. The main difference, however, is that Log Horizon is more forgiving since if the virtual characters of the players die, they’re players do not – the virtual characters simply respawn at the waypoint of the last city they were at – the Cathedral. Dying, however, carries significant and increasingly severe penalties such as losing EXP, potentially losing items carried during death, and a more sinister penalty not openly explained – memory loss. When player characters die in-game, they lose memories of their lives back in the real world. Their consciousnesses tying themselves to their real-world brain-function lose parts of the memories of who they once were. So even in a system where death is impermanent, respawning still carries inherent risk.

In the world of Log Horizon, engaging in PK was an option that some chose for different reasons: boredom, thrill , or the lure of quick profit through looting other players’ equipment. Early on, many players didn’t fully grasp the darker side of PK-ing because it was assumed that death was impermanent and was simply an inconvenience with the respawn system in place. However, as laid out above, this was not the case. There are many hidden costs to PK-ing from a moral and ethical standpoint. What is more important, you advancing through the ranks of the playerbase through any means necessary or your potential victims retaining the progress they made in the game and the memories they had of the world that was left behind? As a potential PK-er that is a question you must ask yourself.

The first kind of willful murder, also known as premeditated murder, is known as First-Degree Murder. This is when there is intent to kill combined with malicious and purposeful planning. A second type of murder that also falls under willful murder but lacks the element of premeditation is Second-Degree Murder. This is the result of impulsive violence resulting in involuntary murder. The third kind of murder, third-degree, is generally not viewed as willful in the sense that there is intent to kill. This kind of murder arises from unplanned and unintentional consequences of potentially lethal actions such as providing or administering drugs which have life-threatening adverse effects if not administered or taken properly.

A readily available real-world theological example for first-degree murder: the tale of Cain and Abel featured in holy texts of the Abrahamic faiths. While anachronistic, this prominent tale highlights an example of premeditated murder undertaken by someone against his own kin primarily motivated by envy.

The consequences of Cain’s actions culminating in the first murder in the world have multiple consequences:

- Alienation from friends, family, and any close acquaintances – Cain was cursed to wander as a fugitive.

- Divine Punishment in the form of a mark placed upon Cain – Perpetuation of a vicious cycle of aggression due to God’s mark bringing down sevenfold punishment upon anyone who commits the same offense of bringing violence down on another’s life.

- Introduction of a transgression into the history of the world, staining it with impurity.

- It was also said that the soil was cursed for it “drank the blood of Abel”.

The modern-day mythology of Cain even paints him as being the progenitor of Vampires, with this notion being largely popularized by the tabletop role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade. The notion of Cain as the progenitor of vampires in myth doesn’t come from the canonical holy texts of any Abrahamic faith, but from a syncretic mix of folkloric interpretations, non-canonical religious texts, and modern influences from the literary and gaming worlds. As stated above, Cain is known only for acting out the first murder and was thus marked and cursed by God for his brother’s death. Some non-canonical texts, such as “Life of Adam and Eve” show Eve dreaming of Cain drinking Abel’s blood. This minute detail in an apocryphal text combined with God’s canonical multifaceted curse on Cain which marked him as a “fugitive” and a “wanderer”, while simultaneously also placing upon him a mark which would confer upon him divine protection from death at the hands of others, offer a foundation to the proto-vampiric myth of an immortal wandering blood-drinker.

The modern incarnation of the myth, wherein Cain is seen as the first vampire or the progenitor of a vampiric lineage, was due in large part to contemporary role-playing games. The most notable of these within the context of Cain’s portrayal as the first vampire is White Wolf Publishing’s Vampire: The Masquerade. In these works, Cain is explicitly linked to vampirism and even has connections to the mythological figure of Lilith. The concept of Cain as a vampire progenitor, however, is older than Vampire: The Masquerade, with some modern literary works exploring it before the role-playing game solidified the connection. An example of this would be George R. R. Martin’s Fevre Dream.

- For a more somber and non-fantastical look at the act of committing violence against others, we can also look at the infamous cases of murder in real life worldwide:

The Assassination of Julius Caesar (44 BCE): a politically motivated homicide carried out by Roman senators contributed significantly to the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. - The Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (1865): The assassination carried out by John Wilkes Booth during the nation’s turbulent post-Civil War period marked a turning point in American history. This case altered the course of Reconstruction and set precedents in how politically motivated homicides are investigated and tried.

- Jack the Ripper (1888): Operating in the Whitechapel district of London, this unidentified serial killer is known for a series of brutal murders of prostitutes.

- The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (1914): While a single event, the killing of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip was the critical spark that ignited World War I, a conflict that reshaped the world map and global politics.

- The Manson Family Murders (1969, Los Angeles): Orchestrated by cult leader Charles Manson, these killings targeted well-known figures such as actress Sharon Tate. The case raised profound questions about influence, group psychology, and violence .

- The Zodiac Killer (Late 1960s – Early 1970s): This still-unidentified serial killer terrorized Northern California, communicating with the police and press through taunting letters and complex ciphers.

- The Assassination of John F. Kennedy (1963): The murder of the 35th President of the United States in Dallas remains a deeply impactful and controversial event in American history.

- Dennis Nilsen (Late 1970s–Early 1980s): Infamously dubbed a “chronic executioner,” his series of killings and post-mortem manipulations shocked Britain. His case remains notable for its disturbing details and the manner in which it exposed vulnerabilities in the systems meant to protect society’s most at-risk individuals .

- John Wayne Gacy (1970s): Often referred to as the “Killer Clown” because of his community role as a party entertainer, Gacy was responsible for the murders of at least 33 young men. His case is one of the most infamous examples of serial killing in American history and has had a lasting impact on discussions of criminal psychology and forensic science .

- Ted Bundy (1970s): Bundy’s manipulative charm and horrifying crimes made him one of the most notorious serial killers of his time.

- David Berkowitz – “Son of Sam” (1970s): Berkowitz’s spree of seemingly random shootings terrorized New York City, leaving a legacy of fear and profound changes in police investigation techniques. His case remains a key study in the patterns and triggers of serial homicide .

- Diane Downs (1983): In a case that stunned the nation, Diane Downs was convicted of shooting her own children.

- The O.J. Simpson Case (1994-1995): While more recent, the trial of O.J. Simpson for the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman was a landmark case due to the defendant’s celebrity status, the intense media coverage, and the significant social and racial tensions it brought to the forefront in the United States.

- The Murder of Gianni Versace (1997): The killing of the iconic fashion designer Gianni Versace brought together the worlds of celebrity, crime, and media spectacle. The high-profile nature of the case, coupled with the dramatic circumstances of the murder, ensured its enduring place in discussions of modern homicides.

- Katherine Knight: Known as one of Australia’s most notorious criminal cases, Katherine Knight was convicted for the brutal murder—and subsequent dismemberment—of her partner.

Now let’s explore the potential motivations that could drive someone to engage in homicide. First, we can examine clusters of cases that share common themes or underlying motives. Each homicide is unique, but many exhibit overlapping psychological or ideological elements:

Serial Killers with Repetitive, Predatory Patterns

Notable Cases: John Wayne Gacy, Ted Bundy, David Berkowitz (“Son of Sam”)

Common Themes and Motives:

– Serial Predation: All three engaged in a series of murders over extended periods, driven by a compulsive need to kill.

– Psychological Gratification: Their acts frequently involved sexual or sadistic elements, where the act of killing provided a perverse sense of power or control.

– Community Facades: Each maintained a publicly acceptable life (Gacy as a community entertainer, Bundy as a charming persona, Berkowitz with a seemingly ordinary background) that contrasted sharply with their secret violent lives.

– Media Impact: They have all fueled a societal fascination with the psychology behind serial killers, influencing both criminal profiling and public discourse on the nature of evil.

Homicides Within Intimate or Domestic Settings

Notable Cases: Diane Downs (killing her own children), Katherine Knight (killing and dismembering her partner)

Common Themes and Motives:

– Betrayal of Trust: The violence unfolds in deeply personal relationships where trust is paramount.

– Psychological Disturbance: Their actions hint at profound disturbances in personal or familial bonds, with perpetrators acting out against those closest to them.

– Social Shock: The betrayal inherent in domestic homicides often leaves communities grappling with a mixture of horror, empathy, and disbelief, raising debates about the nature of trust and vulnerability in intimate relationships.

Ideologically or Cult-Driven Violence

Notable Cases: The Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, The Manson Family Murders

Common Themes and Motives:

Although these two types of cases operate in different arenas, they share a core element: the motivation to commit violence is driven by extreme beliefs.

– Lincoln’s assassination was a politically charged act aimed at influencing the direction of a nation during a time of immense turmoil.

– The Manson Family murders were executed as part of a cult’s radical vision, where violence was seen as a catalyst for an apocalyptic societal transformation.

– Impact on Social Order: Both cases not only aimed at the individual victims but also sent ripples through society, prompting reflections on political dissent, ideological extremism, and the boundaries of influence.

Understanding what drives someone to take another life is a profoundly complex issue, as motivations for homicide tend to be multi-dimensional and layered. Here’s an in-depth exploration of these motivations:

Many homicides occur in moments of intense emotional arousal. These are often categorized as reactive or impulsive killings where an individual, overwhelmed by anger, jealousy, or feelings of betrayal, commits an act in the heat of the moment. The emotional disturbance can suddenly override rational thought, leading to tragic consequences.

When individuals perceive a deep injustice—whether from personal betrayal, humiliation, or long-standing resentment—they may commit homicide as a form of retribution. In such cases, the act is less about a premeditated plan and more about an uncontrollable urge to “balance the scales” after a perceived wrong.

When individuals perceive a deep injustice—whether from personal betrayal, humiliation, or long-standing resentment—they may commit homicide as a form of retribution. In such cases, the act is less about a premeditated plan and more about an uncontrollable urge to “balance the scales” after a perceived wrong.

In some cases, homicide is not primarily about emotion but about achieving a specific objective. This can include eliminating competitors, engaging in contract killings, or other criminal enterprises where the act of killing is a means to secure economic or material advantage.

Certain perpetrators are driven by a compulsive need to dominate or control others. In some serial killings and domestic violence cases, the act is less about a situational trigger and more about exerting authority and reinforcing a sense of superiority. This instrumental use of violence often manifests in cold, premeditated acts where the victim is seen merely as an object for the perpetrator’s gratification. Research often shows that these calculated forms of homicide are underpinned by distorted cognitions and a skewed sense of entitlement, where the offender views murder as a valid tool to achieve personal goals.

There are homicides committed as expressions of extremist social or political beliefs. High-profile assassinations or cult-driven murders, for example, are aimed not only at eliminating an individual but also at sending a broader message or sparking societal change. Such acts are usually wrapped in symbolism and intended to resonate on a national or even global scale. In environments where gang affiliations run deep, homicide might be influenced by rivalries, territorial disputes, or social pressures to conform. These killings are often not isolated incidents, but part of a larger pattern of violence within or between groups, where honor, reputation, and survival are at stake.

In some cases, underlying psychological disturbances can play a critical role. Conditions such as severe personality disorders, psychopathy, or other mental illnesses might impair judgment and increase propensity toward violence. These individuals may lack empathy or exhibit impulsivity, making them more likely to cross the line into lethal aggression. Elevated levels of stress, combined with factors such as substance abuse, can exacerbate aggressive tendencies. Research has shown that individuals with poor coping mechanisms, low self-esteem, or limited social support are at greater risk of resorting to extreme violence when confronted with challenging situations.

Studies linking individual psychological profiles to homicidal behavior emphasize that it is rarely a single factor but a convergence of internal vulnerabilities and external pressures that tip the balance toward violence. It’s important to recognize that these categories are not mutually exclusive. Many homicides emerge from an intricate interplay of multiple factors—emotional distress might intertwine with a desire for control, or ideological beliefs might be driven by personal traumas. This complex mosaic makes comprehensive profiling challenging but also vital in forensic investigations, legal proceedings, and ultimately, in efforts to prevent future violence.

Understanding these motivations not only aids in grasping why homicides occur but also informs strategies in law enforcement, mental healthcare, and community support aimed at reducing the incidence of such tragic events. To delve even deeper, one might explore how early intervention in mental health, effective conflict resolution training, and robust social support systems might mitigate some of these risk factors.

Now, let’s take the questions that a PK-er could potentially ask themselves before performing violence on another and apply them to real-life potential killers:

- Is murder my first or last option in this scenario? Why or why not?

- During times when I feel that murder is the only course of action left, is there really no other method I can come up with to tackle the problem I believe I am solving through murder?

- What if I personally know the person I am about to kill? Would that make a difference? Why or why not?

- Would thinking about the friends and family of my potential victim convince me to try a different method closer to non-lethal neutralization? Why or why not?

- What if the person I am about to kill holds some degree of importance to an organization I belong to? What if their sudden death causes turmoil and potential suffering for others that I care about in the near future? Are my reasons for engaging in murder still justified?

Psychopathy

Psychopathy, a condition with the absence of empathy as one of its most defining features, is something that killers in both the real and virtual worlds tend to exhibit. They also exhibit blunting of other emotions, yet are able to outwardly project affect in order to put on an act for personal gain. This absence of empathy leads to callousness, which is defined as a cruel and insensitive disregard for others. They then also tend to show emotional detachment. All of these qualities act in concert to bring out a psychopath’s manipulative side. At its most basic, lying in order to get something you want is a manifestation of manipulation. Going back to the Abrahamic tale of Cain and Abel, we can see this when he lures his brother to an area where he is able to commit the first murder in the Abrahamic history of the world.

The current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the reference text used by mental health professionals when it comes to clinical diagnoses of mental illness, does not officially have specific diagnosis for the phenomenon of psychopathy. In lieu of this, conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder are discussed below as these two do have official diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5.

Conduct disorder is described as a repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or major age- appropriate societal norms or rules are violated, as manifested by the presence of at least three of the following criteria in the past 12 months, with at least one criterion present in the past 6 months (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

Aggression to People and Animals – Physical, verbal, or psychological aggression against others manifesting as bullying, threatening, intimidating, and being violent towards humans and animals. It can also manifest in the taking from others’ by force or coercion – stealing from others through force or even coercing another into sexual activity.

Destruction of Property – Deliberate destruction of others’ property, vandalism, as well as deliberate and intentional arson.

Deceitfulness or Theft – Constitutes action such as breaking into another’s property, lying to obtain good or favors, lying to avoid obligations, and stealing items of nontrivial value without the victim becoming aware.

Serious Violations of Rules – The specific behaviors indicated here are running away from home, staying out at night against the wishes of one’s parents, and the tendency to intentionally not attend compulsory education.

Also important for clinical diagnosis is that the disturbance in behavior causes clinically significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning.

A significant specifier for this condition would be “with limited prosocial emotions”. This essentially is the difference between someone who could readily be taught to channel their energy towards good for society, or someone who will be resistant to doing so. The following characteristics must be persistently displayed over multiple settings by a person:

Lack of remorse or guilt: One will show lack of remorse or concern about the negative consequences of their actions. A notable exclusion to this is remorse expressed only when caught or facing punishment.

Callous – lack of empathy: This is when someone disregards and is unconcerned about the feelings and wellbeing of others. They will be more concerned about the effects of their actions on themselves, rather than their effects on others, even when those actions result in substantial harm to others.

Unconcerned about performance: This is when an individual does not show concern about problematic performance at school, work, or in other important activities.

Shallow or deficient affect: This is when someone tends not to outwardly express feelings except in ways that seem shallow, insincere, or superficial, or when emotional expressions are used for gain, such as when emotions are expressed with the intent to manipulate or intimidate others.

Source: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Next we have Antisocial Personality Disorder Diagnostic Criteria, or ASPD for short. It is described as a pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others, occurring since age 15 years, as indicated by 3 (or more) of the following (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

- Failure to obey laws and norms by engaging in behavior which results in criminal arrest, or would warrant criminal arrest

- Lying, deception, and manipulation, for profit or self-amusement,

- Impulsive behavior

- Irritability and aggression, manifested as frequently assaults others, or engages in fighting

- Blatantly disregards safety of self and others,

- A pattern of irresponsibility and

- Lack of remorse for actions

Another important thing to note is that this antisocial behavior does not occur in the context of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Source: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Clinical psychopathy as a construct is used to describe a distinct personality syndrome characterized by deviations in affect, interpersonal relationships, and contextual behaviors that constitute a marked departure from baseline normality found in the human population. The book The Mask of Sanity by Hervey Cleckley laid the groundwork for understanding psychopathy as a unique clinical entity beyond just criminality. Robert Hare refined this concept into a measurable format via the Psychopathy Checklist—Revised (PCL‑R). This is more used in forensic settings, as opposed to clinical settings wherein the DSM-5 criteria for antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) or conduct disorder. Contemporary views on the phenomenon of psychopathy is skewed towards perceiving it as a construct that encompasses specific affective and interpersonal deficits like lack of empathy and superficial charm that may at times go beyond the behavioral criteria listed for ASPD.

There are two primary factors that comprise the conceptual construct of clinical psychopathy – difficulty connecting with others (interpersonal and affective deficits) and exhibiting tendencies to go against societal norms while causing harm to others (antisocial behaviors). An individual who has difficulty connecting with others at an emotional level may exhibit behaviors such as superficial charm, manipulativeness, emotional shallowness, callousness, and a lack of remorse. These reflect a profound deficit in empathy and a tendency to exploit others for personal gain. Next, an individual who has a tendency to go against societal norms exhibit impulsivity, a parasitic lifestyle, poor behavioral controls, and predisposition toward criminality or rule-breaking.

- Interpersonal Facet:

- Glibness/Superficial Charm: Smooth, engaging, entertaining conversationalists, often seem too good to be true.

- Grandiose Sense of Self-Worth: Arrogant, entitled, inflated view of their abilities and importance.

- Pathological Lying: Deceitful, dishonest, can lie easily and convincingly, often for no apparent reason.

- Conning/Manipulative: Use deceit and trickery to achieve their own ends, view others as pawns.

- Affective Facet:

- Lack of Remorse or Guilt: Indifferent to the negative consequences of their actions on others, no feelings of guilt or regret.

- Shallow Affect: Limited range and depth of emotional responses; emotions often seem feigned or short-lived.

- Lack of Empathy: Cold, callous, unable to understand or share the feelings of others.

- Failure to Accept Responsibility for Actions: Blames others, external circumstances, or minimizes the impact of their behavior.

- Lifestyle Facet:

- Need for Stimulation/Proneness to Boredom: Constant need for excitement, thrill-seeking, low tolerance for routine or boredom.

- Parasitic Lifestyle: Reliant on others for financial support, often exploiting kindness or generosity.

- Poor Behavioral Controls: Easily angered, reactive, short-tempered, aggression may be poorly controlled.

- Lack of Realistic Long-Term Goals: Unstable life plans, often live day-to-day.

- Impulsivity: Act without thinking about consequences.

- Irresponsibility: Repeated failure to meet obligations (work, financial, interpersonal).

- Antisocial Facet:

- Early Behavioral Problems: Conduct issues evident from a young age (e.g., lying, cheating, aggression, property damage).

- Juvenile Delinquency: Criminal behavior during adolescence.

- Revocation of Conditional Release: Violations of probation, parole, or other supervised release.

- Criminal Versatility: Commits a wide variety of criminal offenses, not specializing in just one type.

Some debate has been had by scholars about whether psychopathy is best understood as a categorical disorder or as a dimensional trait that varies in intensity across the population. The categorical interpretation leads to a binary view about whether a person truly is a psychopath or isn’t. Scholars have increasingly favored a dimensional approach, reflecting evidence that many psychopathic traits exist in the general population on a continuum.

The most prominent tool for assessing psychopathy in both clinical and forensic settings is the PCL-R, a semi-structured interview tool that relies on both self-report and collateral information such as criminal history. It can be used to make informed decisions about risk management, treatment suitability and the likelihood of relapse into harmful behavior. Despite being controversial, it exhibits robust predictive validity regarding potential future antisocial behavior of an individual.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed abnormalities in several key brain regions linked to emotion regulation and impulse control, such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex wherein reduced structural and functional connectivity in these areas is thought to underpin the marked deficits in empathy and decision-making seen in psychopathy (Mika et al, 2019) . Researchers also note that adverse early-life experiences—combined with a genetic predisposition—can contribute significantly to the development of the disorder. In this vein, psychopathy serves as a compelling example of how biological vulnerabilities and environmental stressors can interact to produce complex behavioral phenotypes (Frazier et al, 2019).

There is a crucial distinction often confused between ASPD and Psychopathy. ASPD is a diagnosis listed in the DSM-5 and is primarily defined by a pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others, manifested largely through observable antisocial behaviors. Many of these align with PCL-R Factor 2. Psychopathy, as diagnosed through the PCL-R, is a research and clinical construct that emphasizes the interpersonal and affective deficits (PCL-R Factor 1) in addition to the antisocial behaviors in Factor 2. Most individuals who score high on the PCL-R meet the criteria for ASPD. However, the majority of individuals diagnosed with ASPD do not score high enough on the PCL-R to be considered psychopathic.To put it another way: All clinical psychopaths might be considered to have ASPD, but only a subset of those with ASPD are psychopaths. Psychopathy represents a more severe and specific group characterized by profound emotional unresponsiveness and manipulative interpersonal style, which ASPD criteria alone do not fully capture.

Can Psychopathy be weaponized? There are fictional examples of this being the case as in the storyline of Batman: The Black Mirror when James Gordon Junior, the son of Commissioner Gordon, inverted the formula of the fictional drug Diaxamyne to induce psychopathy in individuals instead of treating psychopathy. Psychopathy being induced in vulnerable populations could create a crop of wolves in sheeps’ clothing among the target population which could ultimately lead to its destruction down the line if led to commit violence amongst themselves.

On the flip side, could psychopathy be used for prosocial causes to help benefit the world at large? That is one of the arguments of the book Wisdom of Psychopaths wherein author Kevin Dutton chronicles in detail how a certain degree of psychopathy can aid in endeavors that benefit society. The book highlights traits often found in psychopathy that can be seen as positive or functional in certain contexts, such as fearlessness and calmness under pressure, ruthless efficiency and decisiveness, charm and charisma, focus and mindfulness in the moment, lack of emotional baggage holding them back. Dutton further distinguishes between high-scoring psychopaths who engage in destructive, criminal behavior (dysfunctional) and individuals who possess some psychopathic traits but channel them into successful, non-criminal careers (functional). Examples of non-criminal careers where these traits might be particularly useful would be in surgeons (requiring calmness under pressure), CEOs (requiring decisiveness and ruthlessness), lawyers, special forces soldiers, and even in seemingly ordinary situations requiring boldness or resilience.

A more specific example of a setting wherein a degree of psychopathy could be prosocial and helpful would be in how professional athletes participate in high-stakes competitions. The Nike advertisement “Winning isn’t for everyone” shows that a touch of psychopathy is necessary to ensure an individual is oriented towards success in competitive landscapes. This also applies to other endeavors where competition is a key element such as business and warfare.

A provocative idea in the book is “Learning from the Dark Side”. This refers to whether or not normal neurotypical individuals can strategically adopt or cultivate some of these psychopathic traits in limited doses to improve their own lives, careers, or ability to handle stress, all without becoming full-blown dysfunctional psychopaths.

A thematic and relevant analogy in the book is that of sunlight – just as a moderate amount of sunlight is essential for biological growth and sustenance but too much can result in sunburns and skin cancer, the moderate presence of psychopathic traits may empower an individual by fostering decisiveness and resilience. Dutton bolsters his arguments with empirical research and historical examples, drawing from a range of studies in psychology and neuroscience. The interdisciplinary approach used in the book not only deepens our understanding of personality but also suggests that many qualities we often condemn might, under the right conditions, be harnessed to achieve success in areas like emergency services, business leadership, military operations and even creative endeavors.

Impact of PK/murder on the victim:

- Irreversible loss of life of the victim, cutting short their ambitions, relationships, and contributions to society.

- Family and friends of victims irreversibly lose the person they care for, and they experience intense grief, trauma, and sometimes long-term psychological distress such as PTSD or depression.

- Failure to complete PK/murder results in potentially life-debilitating injury and psychological trauma within victims, as well as the financial burden of treatment

- The murder can fracture social circles, leading to changes in dynamics, mistrust, and sometimes even retaliation cycles in violent environments.

- Funeral costs, legal proceedings, and potential loss of financial stability (if the victim was the primary provider) add stress.

- High-profile cases may influence legal reforms, public safety measures, and even cultural narratives around justice and crime.

Impact of PK/murder on the aggressor:

- Risk of punishment by the criminal justice system.

- Some murderers feel remorse, leading to guilt-induced anxiety or even suicidal ideation. Others experience reinforcement of violent tendencies or detachment, especially in cases of serial or ideological killings.

- Loss of personal freedom, severed relationships, and long-term stigma mean even those who escape conviction often live under scrutiny or exile.

- Some murderers, especially those driven by psychological disorders or ideological beliefs, may continue violent behaviors without intervention.

Societal implications of willful violence against others

- Investigations, trials, and prison systems deal with immense logistical burdens, often leading to systemic debates about sentencing, rehabilitation, or capital punishment.

- Creates fear and insecurity, erodes trust, highlights societal issues (e.g., crime rates, mental health, access to weapons). Results in the loss of a civilian life and the cost of managing the perpetrator within the legal system.

- Murder cases, especially sensationalized ones, shape public perception of crime, influencing law enforcement policies, societal fears, and even entertainment tropes.

- Society grapples with moral debates surrounding justice, rehabilitation, and the nature of evil, often questioning whether murder is driven by external circumstances or intrinsic predisposition.

- Devastating grief, trauma, psychological distress, potential financial hardship, and a long process of seeking justice and healing.

What about armed fighters on either side of a conflict? Soldiers who kill in order to defend, and terrorists who kill in order to incite terror? Though, not all is black and white with some soldiers committing atrocities themselves and some terrorists being forced into fighting out of desperation. I believe these complexities deserve their own article and thus will write about it in the future.

What about genocide? What are the implications of impersonal and widespread snuffing out of lives? How is accountability distributed in this scenario? How much weight will be borne by the architect of the mass-slaughter, the officers who put the mass-slaughter into motion, and the footsoldiers following orders? I also believe this warrants its own article and will thus write about it in the future.

The following two psychology studies have given insights into the nature of human morality.

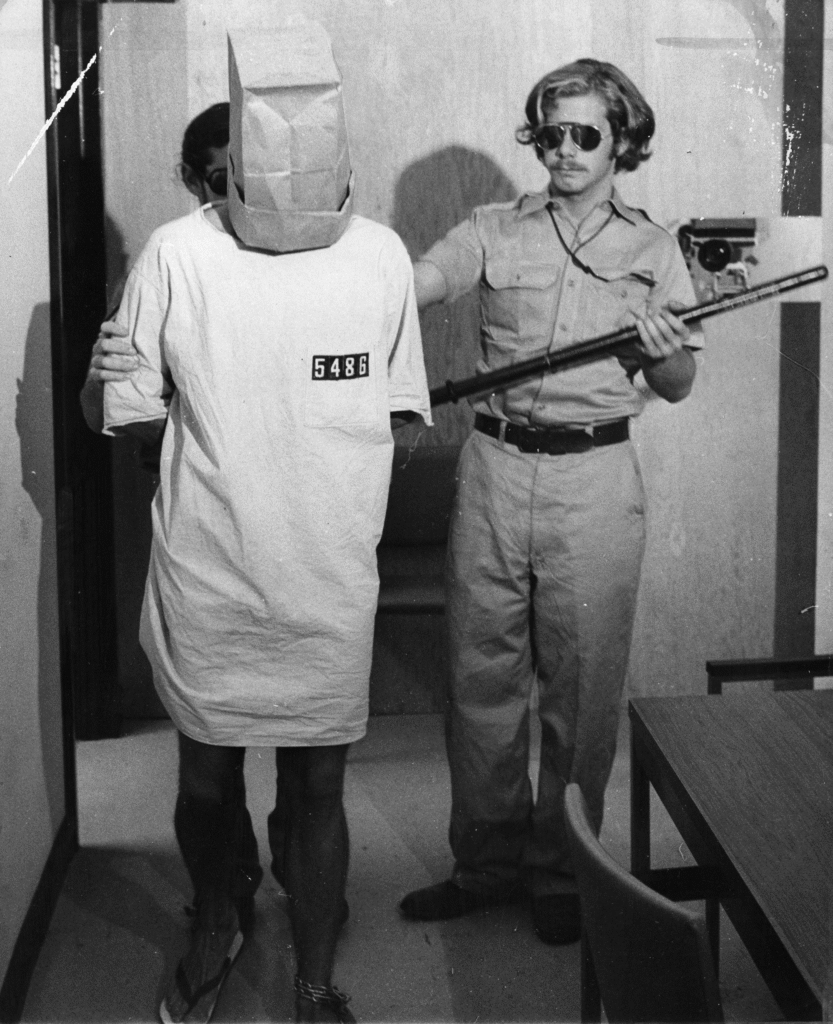

First off, we have the Stanford Prison Experiment. The Stanford Prison Experiment was a landmark study in social psychology that still captivates both academics and popular psychology alike. Psychologist Philip Zimbardo set out to explore how ordinary people might behave when thrust into extreme roles—in this case, as either “prisoners” or “guards” in a simulated prison environment. In the experiment, college students volunteered to participate and were randomly assigned to either role. Almost immediately, the “guards” began to exhibit authoritarian behaviors, while the “prisoners” quickly fell into patterns of submission and even distress. What started as an exploration of role conformity soon spiraled into a situation where the environment’s impact on behavior became alarmingly clear. The guards, given power without sufficient oversight, enacted increasingly oppressive measures—highlighting how easily power can corrupt—even among individuals who might otherwise be considered normal in day-to-day life.

Despite having academic intentions, the implications of the Stanford Prison Experiment are both accessible and profound. It demonstrates that when social roles are rigidly defined and unchecked authority is allowed to flourish, even well-intentioned people can engage in harmful behaviors. For the participants, the experience was transformative and, for many, traumatic—underscoring the heavy human cost that sometimes accompanies experimental research. Ethically, the study raised serious questions about the limits of research, informed consent, and the responsibilities of scientists to protect their subjects.

Today, the experiment isn’t just a historical footnote. It has fueled ongoing discussions about authority, conformity, and the psychology of power—a dialogue that remains incredibly relevant whether you’re a psychology student, a professional in the field, or simply a curious reader. Its story serves as a dramatic reminder that context and environment can dramatically alter how people behave, nudging everyone to reflect on where the line lies between role-playing and real-world consequences.

Secondly, we have the Milgram Shock Experiment. The Milgram Shock Experiment gave insights into authority, obedience, and human morality even decades after it was conducted. Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram devised this experiment to explore the extent to which ordinary people would obey authority, even when asked to perform actions that conflicted with their personal conscience. This was conducted in the aftermath of World War II and the trials of Nazi officials, where the defense of “they were just following orders” raised harrowing ethical questions.

Participants were told they were taking part in a study on learning and punishment. They were assigned the role of “teacher,” while another person was assigned the role of “learner.” Unbeknownst to the participants, the learner would actually be a paid actor. The learner was placed in another room and hooked up to what appeared to be a shocking device. The teacher was instructed to administer electric shocks whenever the learner gave incorrect answers—each time increasing the voltage, with labels ranging from Slight Shock to Danger: Severe Shock.

There weren’t actually any real shocks in the experiment. But the learner—acting according to a script—would cry out in distress, bang on the walls, and eventually stop responding altogether. The real participant, sitting in front of the machine, had a choice: continue following orders from the stern-looking experimenter or refuse.

What Milgram found was startling. 65% of participants continued to administer the supposed shocks all the way to the maximum voltage, even after the learner’s protests had ceased. Many showed signs of extreme distress—hesitation, nervous laughter, and visible anxiety—but when urged by the authority figure with simple phrases like “The experiment must continue,” they obeyed.

This study demonstrated that ordinary people, when placed in a structured environment with an authoritative figure, are capable of committing harmful actions they might otherwise never consider. The implications of Milgram’s experiment extend far beyond the lab: it provides insight into everything from historical atrocities to workplace dynamics and how institutions wield authority over individuals.

Critics have pointed out ethical concerns regarding the emotional strain placed on participants, leading to evolving standards in psychological research. But regardless of where one stands on ethics, the experiment remains a powerful reminder of how easily authority can override personal judgment—and how important it is to question directives, even when they come from those in charge.

The enduring legacy of Stanley Milgram’s shock experiment continues to resonate today by challenging us to reflect on the nature of authority, obedience, and personal responsibility in any society. Originally designed to explore how far individuals might go in following orders—even when such orders defy their ethical beliefs—the experiment underscores a fundamental vulnerability in human behavior. This understanding invites us to rigorously examine modern power structures, where the lines between moral autonomy and blind submission can blur in unexpected—and sometimes dangerous—ways.

One modern implication lies within organizational and institutional settings. Hierarchical structures in workplaces, the military, and law enforcement can sometimes foster environments where subordinates follow unethical directives simply because they trust the legitimacy of authority. This insight is particularly relevant today, as employees and citizens question decisions made by those in power. The experiment encourages us to design systems where accountability is embedded at every level, ensuring that no individual feels compelled to relinquish their moral judgment simply by deferring responsibility to a superior.

The digital age further expands the reach of Milgram’s findings. In an era marked by algorithmic governance, we see new forms of authority—through social media platforms, data-driven decision-making, and artificial intelligence—that subtly guide individual actions and opinions. While these systems might seem impartial, they can influence behavior and propagate ideologies without people consciously realizing it. Just as participants in Milgram’s study deferred moral responsibility to an authority figure, modern users might yield to the “invisible hand” of digital networks, raising questions about autonomy and the manipulation of public opinion.

Another significant outcome of Milgram’s work is its impact on ethical standards in research and beyond. The controversy surrounding the experiment’s use of deception and the resulting psychological stress imposed on participants served as a catalyst for substantial ethical reforms. Modern institutional review boards and ethical guidelines now emphasize informed consent, the right to withdraw, and the minimization of harm—principles that not only protect research subjects but also remind us that unchecked obedience can have harmful consequences in any sphere of life.

Finally, the implications reach into the political realm, where the dynamics of authority can result in collective actions that may conflict with individual moral convictions. The lessons of Milgram remind us that fostering critical thinking and personal responsibility is essential for resisting authoritarian temptations. By actively engaging in civic education and encouraging ethical skepticism toward those wielding power, societies can safeguard against the kind of destructive obedience that has, in the past, led to grave injustices.

One might wonder, given these reflections, what new forms of authority are emerging in our digitally interconnected world? How might modern technologies—especially those that operate with subtle persuasion algorithms—reshape our understanding of obedience and conformity? Exploring these questions further could yield rich insights into both the potentials and pitfalls of our current social fabric.

References:

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Frazier, A., Ferreira, P. A., & Gonzales, J. E. (2019). Born this way? A review of neurobiological and environmental evidence for the etiology of psychopathy. Personality neuroscience, 2, e8. https://doi.org/10.1017/pen.2019.7

- Mika, J., Olli, V.., Jari, T., & Markku, L. (2019). A Systematic Literature Review of Neuroimaging of Psychopathic Traits. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 1027. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01027